The following interview with Rob Fersh and Mariah Levison has been edited and condensed. You can learn more about From Conflict to Convergence: Coming Together to Solve Tough Problems and pre-order the book here.

Rob Fersh founded Convergence in 2009 and served as its first CEO until 2020. He has spent over 45 years bridging policy differences and moving important public policy solutions forward in Washington D.C., working for Congress, in the Executive Branch, and in leading non-profit organizations.

Mariah Levison, Convergence CEO and President, is a seasoned consensus-builder with decades of experience in bringing people together to solve critical issues, with expertise spanning assessment, design, facilitation, mediation, collaborative processes, dialogue, public engagement best practices, restorative justice, and program development.

What inspired you to write a book about collaboration?

Over the past few decades, we have had the privilege of seeing over and over again people who seem hopelessly divided building trust and forging consensus on seemingly intractable issues.

Today, as we constantly hear about how divided our nation is and how daunting our problems are, we wanted to share our stories and provide hope that we aren’t as divided as it seems and that there are ways to work together to solve our shared problems. We also wanted to equip ordinary citizens and the many leaders in all sectors struggling with managing division – whether among employees in the workplace or constituents at a city council meeting. This book provides evidence-based tools to help them forge higher-ground solutions that not only solve problems in their communities and organizations but also help to strengthen our democracy.

There are more and more books and articles now about “bridging” divides that really are terrific. Yet, we felt there was a gap in the literature in terms of explaining the power of and the best approaches to helping people work across differences to go beyond bridging disparate opinions to actually solving problems.

You are co-authors of this book. How did your experience at Convergence inform your collaborative writing process?

Who, us? Collaborate? What were you thinking when you asked this question?

Practicing collaborative problem-solving on a wide range of public issues has been the central professional concern for both of us for over two decades. Despite differences in our age, location, and experience, we have arrived at very similar insights and conclusions about how people can work together more effectively across differences, especially on complex issues. We wanted to share what we have learned to help inspire and equip a wide range of people to become more effective collaborators in their work and personal lives. We believed that together we could produce a book better than either of us could generate individually. While we certainly had differences of opinion in writing the book, we were able to use what we have learned to successfully resolve them.

We also continue to collaborate on the leadership of Convergence Center for Policy Resolution, which Rob founded and now serves on the Board of Directors, and which Mariah now leads.

Mariah, what was the moment that made you realize that in most cases, people’s poor behavior in conflicts was an attempt to fulfill one of their basic human needs? How did that change your view of conflict, conflict resolution, and collaboration?

I grew up in St. Louis where I was exposed to a lot of poverty and violence. Witnessing so much struggle working in places like juvenile detention centers and homes for parents who had AIDS made it clear to me that a lot of unproductive behavior was driven by people needing a sense of efficacy, security, belonging, or esteem.

These childhood and young adult experiences were reinforced in my conflict resolution work. I ran school mediation programs in the most violent schools in New York City. Those seemingly tough and angry students began their mediation sessions not talking about the fights they were having with each other but with stories of dying relatives, addicted or incarcerated parents, homelessness, and more. They had an underlying concern for safety, just as participants in a Convergence project about public policy on guns did, whether they were supporting gun restrictions or opposing them.

In conflict, whether interpersonal or international, people frequently ascribe nefarious motives to the other side and assume their goals are mutually exclusive. Central to my approach is to use dialogue to help participants discover the unmet needs that are driving the conflict. Identifying these needs is key to resolving the conflict because doing so enables participants to realize that the other side actually has reasonable motives and concerns, and it creates a path forward by addressing each other’s needs.

Rob, the view that “our side” holds the truth and the “other side” is wrong is very prevalent. Was there a person or experience that made you more willing to listen to and learn from the “other side”?

I have had many “aha” moments that opened my eyes to the intelligence and decency of so many people who see the world differently than I do. If I had to choose one, it would be working as the chief staff person for a US House of Representatives subcommittee on nutrition in the mid-1980s. It was a time when there were widespread reports of increasing hunger in the U.S., and our subcommittee had the lead responsibility for this issue for the House.

I was hired by the subcommittee’s then-chair, former US Representative and later Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta, a Democrat. I was congratulated by many progressive friends about the opportunity to work with Mr. Panetta, a rising star in the House. I was also told by the same friends that it would be difficult to work with the then-ranking Republican on the subcommittee, Bill Emerson of Missouri. My friends held no hope for bipartisan cooperation as they viewed Mr. Emerson as a “Reagan Republican.”

The more that people understand about collaboration, the more they will see this is not just about being nice — it is really effective.

My friends could not have been more wrong. The late Bill Emerson was as thoughtful, reasonable, and compassionate as anyone I came across on Capitol Hill or elsewhere. He and Leon Panetta had many policy differences, but in the process of holding field hearings across the country to better understand the extent and causes of the rise in hunger, they formed a strong personal bond and deep respect for each other. For years, they successfully sponsored bipartisan legislation to address hunger-related issues. For me, it was an indelible experience in learning not to stereotype others and to understand that not all wisdom rested with any one ideology or political party.

What do you find to be the most difficult part of collaborative problem-solving? What is the most rewarding?

We think most people would be shocked by how well the process of building trust and solving problems collaboratively works in most cases. It isn’t that it is easy, but it’s rewarding to see people come together to find great answers to big problems that meet a wide array of needs – what we call higher-ground solutions. The more that people understand about collaboration, the more people will see this is not just about being nice. It is really effective.

Depending upon the circumstances, implementing the shared solutions effectively can be the most challenging part of the process. This is less the case if the people in the room — whether they are business or nonprofit leaders, or a mayor or governor — have the authority to put shared recommendations into action. If you are a business leader who has assembled your stakeholders and they reach an agreement, the path to change may occur quite readily and easily. But in the messier world of dealing with public issues where legislative or regulatory policy change is needed, it often requires patience and persistence to create the kind of impact any consensus-building group hopes to achieve.

If the right people are in the room reflecting a wide range of views on how to solve the problem at hand, they often develop solutions that are wiser and more durable than any one group or a bunch of groups who see the world the same way could have come up with on their own. To see people almost invariably emerge from the process as friends and colleagues and to see them shift in how they see each other and work together over time is always deeply inspiring and fulfilling.

With the heightened polarization and divisions in our country today, what do you see as the way forward for our nation?

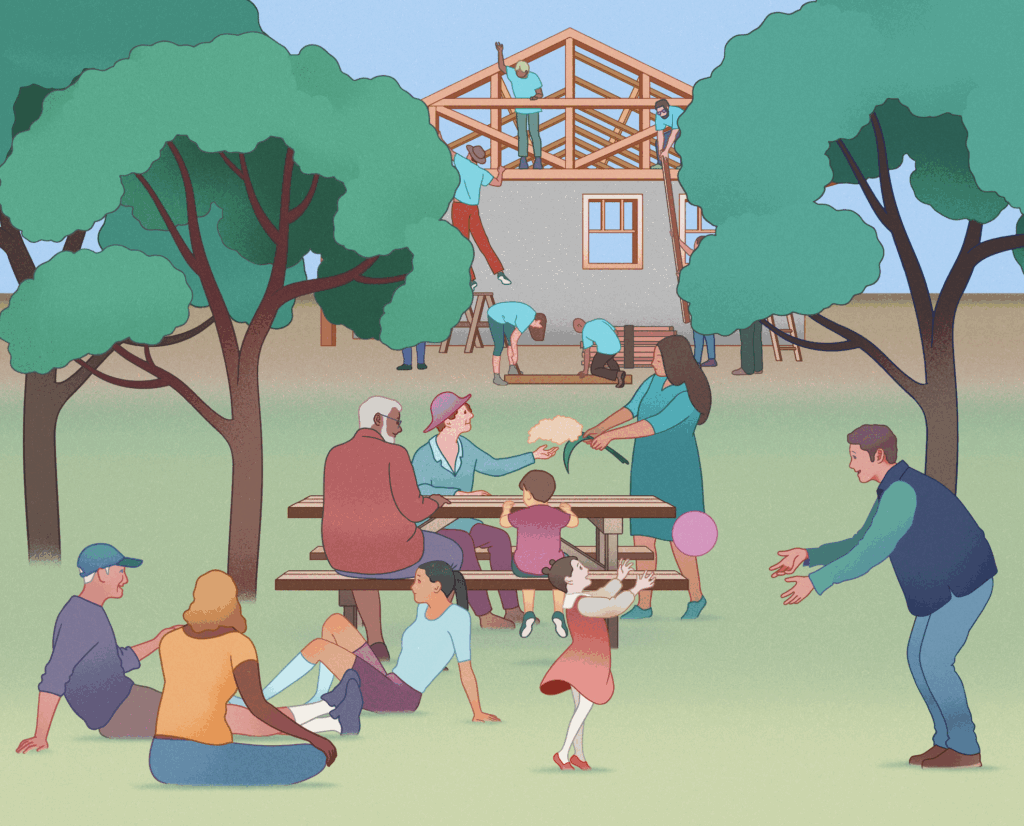

There are many complex factors contributing to polarization and divisions in the U.S., and many people and groups are doing important work to counteract this. In addition to these efforts in such areas as reforming the media and how elections are conducted, we believe that a major doorway to reducing polarization is in normalizing new ways for people who see the world differently to speak to each other and cooperate. Collaborative problem-solving, with its emphasis on putting relationships at the center, can be a key factor in reducing polarization in the country. Not only does it solve problems well, but it has long-term effects on how people see and interact with each other.

If taken to scale — in families, communities, businesses, places of worship, the non-profit sector, and more — collaborative problem-solving can help create a cascading effect with more and more people understanding each other far better and working in greater harmony despite their differences. We want to contribute to a norm where collaboration is employed as a first resort in many settings.

In our polarized world, people have understandably become very concerned about compromising their values. Fortunately, much research and our experience confirm that many of us overestimate the differences in our values. Most people value liberty, equality, compassion, and many other shared values. Collaborative problem-solving provides a path to rediscovering our shared values and developing solutions that go beyond compromise.

The more people choose to work collaboratively and vote for leaders who know how to bring people together to work for a common purpose, the greater chance we have to combat the corrosive polarization unnecessarily dividing a large swath of the country.

Collaboration will not work for all people and in all circumstances, but we strongly believe its full potential is far from being realized.

About Convergence

Convergence is the leading organization bridging divides to solve critical issues through collaborative problem-solving across ideological, political, and cultural lines. For more than fifteen years, Convergence has brought together leaders, doers, and experts—many who never thought they could talk to one another—to build trusting relationships, identify breakthrough solutions, and form unlikely alliances for constructive change on seemingly intractable issues. The honed methodology of Convergence and our experience on issues ranging from prisoner re-entry to generating transformational ideas for K-12 education are central to what we share in this book.